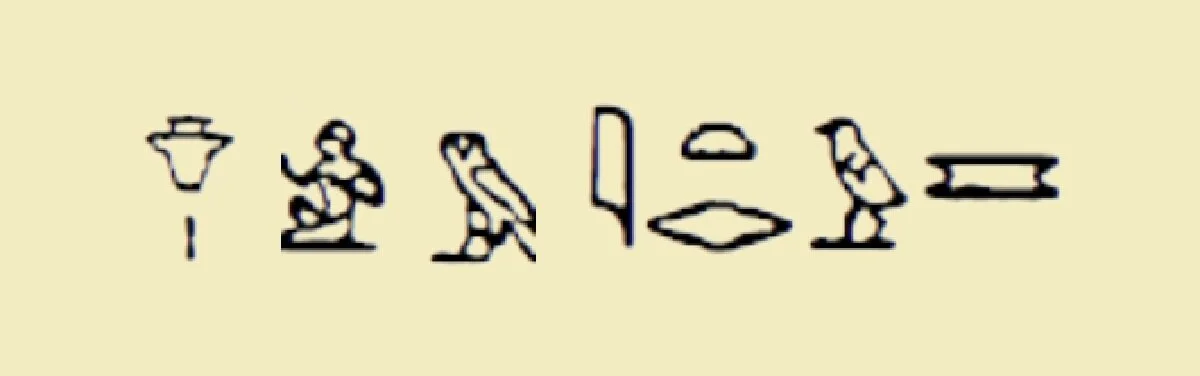

(my heart in the river)

ib.y m itrw

by FJ Doucet

content warning: mention of death

in a year of disease, the museum temple on a toronto street mimics a mausoleum. waves its emptiness like a battle standard repurposed for a shroud. no schoolchildren, boredom and bustle, mill around hermetically sealed portals. i bow my head. sink into white-lit memory of high, echoing halls. for the first time, i saw the wrapped dead, the mummies in the coffins. ten years old, on the knife’s edge of something more perilous than girlhood, i thought i was ready for a global change — a blood shift, a kind of end. the pharaohs, too, thought they were ready. i do not know if all their preparations yielded a full crop in sakhet-iaru1, the fields of reeds. but their crossed arms and luxurious sarcophagi lured me like a pop star’s melismatic soprano: celine dion singing how glorious, how unimpeachable, the skull emptied behind the kohl eyes of a funeral mask. brains caught by a hook and drained into a bowl; body-horror made glamorous by an amber thread of amulets. scarab beetles tucked up neat in thin folds of desiccated flesh. theirs was a hopeful sorcery to deceive death, even as mine: that child who stacked words like sandstone in her bedroom tomb. her jealous claws catch a worn book cover. open the spine to white bone and raw word-matter. secrets still unexhumed. she inclines narrowed eyes, the teeth of her hunger — a vulture’s hunger for rotted things — on malodorous paper. laps up faded greyscale pictures. photographs gravid with thick plaster. paints slathered on tomb walls. rust, emerald, ochre. colors of the earth, buried in the earth with ghost eyes to read them, and all of us — pharoah, paints, girl — alone together in the panting dark. woe, woe! that child is gone. now after thirty winters (not many, i know, for the egyptians), is it confined by the walls of this plague: a scythe named for a ring of light. this quarantine solitude is the priest’s. is the scholar's. is a fearful hand bending the reed pen to papyrus. wound up in the long, ribbon bandages of distance, i test my teeth on another text. seek the bronze-age tool to carve wounds on a microscopic death. Teach yourself Hieroglyphs, a new Book of the Dead for this seeker anointed in cedar oil, even as a pharaonic corpse. here i am now, body perched in a white-sailed boat and my heart in the river: the ancients called it itrw2. i bow my head. consume —phoneme, vowel, consonant — the meat and marrow of the sacred carvings. first say R and draw the mouth, then the word, ren, a name3 to write myself a life (longer than the Nile).

–

Non-English vocabulary is Middle Egyptian, in transliteration from the hieroglyphs. Like Arabic, Middle Egyptian did not record short vowel sounds in its scripts, so much of our present knowledge of vowel sounds in the language are guesses based on the last iteration of the language, Coptic, which was recorded in a Greek alphabet. The language had, however, changed considerably by that time, with a relationship approximate to that between modern Italian and classical Latin. Modern Egyptologist frequently insert an 'e' between consonants for convenience' sake.1 fields of reed (the afterlife for Egyptians judged to be of good character)

2 river, referring to the Nile. The word 'Nile' itself is generally agreed to be derived from Greek and a later addition to the Egyptian linguistic and cultural landscape. 'itrw' still exists in modern Egyptian Arabic as a slightly altered word meaning 'stream' (ترعة).

3 the sound for 'r' is represented by a 'mouth' hieroglyph. R + N (a 'water' hieroglyph) together form 'ren', the word for 'name'.

FJ Doucet's work has appeared in Silver Blade, Eye to the Telescope, Literary Mama, and yolk, among others, and is forthcoming in New Myths and the New Tales of the Round Table anthology. Her poetry was previously nominated for a Pushcart Prize, and is among the nominees for this year's Rhysling Award. She is the current president of the Brooklin Poetry Society, based just outside of Toronto, Canada.